|

| Swan Hotel in 1829. |

The Swan Hotel was a large and dominant coaching inn on the

High Street throughout the eighteenth-century and before. According to Joseph Hill it was an ancient tavern, the land of which stretching across the corner of High and New Streets, and belonged to a family called Rastell during the reign of Henry VIII. Between 1666 and 1688 the landlord of the Swan was Edward Crank, who demolished the old tavern, and built another set back from the street, with a large yard in front for carriages, and erected a row of five smart town houses along the street (seen on the left of the trade card,

above).* The Swan was a

haunt of Samuel Johnson, who wrote in 1755 'I was extremely pleased to find that you have not forgotten your old friend, who yet recollects the evenings which we have passed together at Warren's and the Swan'. Johnson resided in Birmingham in the early 1730s with Edmund Hector (to whom he writes above) at Thomas Warren's bookshop, which situated opposite the Swan at that time, as Warren's shop moved about.

|

| Contemporary colouring of the 1829 card. |

In the 1730s, as the notice below announces, you could catch a stage-coach to London at the Swan at six on a Monday morning, and return 'if God permit' on the Saturday.

Take a journey on the Birmingham to London stage-coach here.

A map of the Swan Hotel was produced for a sale of the property in 1836. Although the hotel survived after this date, many of the extended parts of the property, such as the stables on Worcester Street, were being sold in different lots. The railway came to Birmingham in 1838 with the opening of

Curzon Street Station, and whether prospective buyers would have been aware of the impact of the looming rail network, this was the end of an era for coaching inns like the Swan.

|

| Held at Birmingham Archive. |

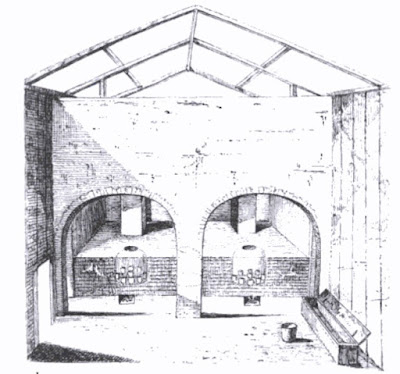

The 'Coach Office', which can be seen in green on the map (Lot 1) on New Street, is depicted in the image below. The street on the right of 'W. JONES', the trunk manufacturer, was Worcester Street, and when the Rotunda was built, this became Worcester Passage, which has now gone itself, but was covered and cut underneath the Rotunda building.

|

New Street (left) at the corner of Worcester Street (right), c. 1840.

By Thomas Underwood, held at Birmingham Archive. |

A later map of the Swan, from the 1850s, shows that the grand open entrance, where the coaches would turn (

as seen in the 1820s trade card), had been built up with new shops, and the hotel itself had been limited to the site behind the New Street Coach Office.

|

| 1850s map showing the Swan Hotel. |

The Twentieth Century Swan

The hotel survived until the late 1950s, but was demolished before 1961 to make way for the new Rotunda. The photos below were taken in 1932 by William A. Clark (

all held at Birmingham Archive).

|

| The swan over the door. |

|

The entrance door with the swan over, looking up

Swan Alley. Note Fred Burn on the right. |

|

| Poor image of the alley from the other direction. Not taken by Clark. |

|

| Landing of the Swan Hotel. |

~ FINIS ~

|

Swan atop the left-hand building of the Hotel in 1800.

From Bisset's directory. |