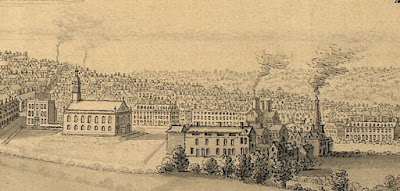

Middleton Hall stood on the corner of - what is now - Woodlands Park Road and Bunbury Road, its land being the site now taken up by Redmead Close. Middleton Hall Road was named after the hall, stretching from Pershore Road to the hall itself, but is a relatively modern addition, being constructed in about 1870. In 1871 about three families lived along it and it was called Middleton Hall Lane.

The area around the Hall, including the Tenants estate, was part of Northfield until the 1920s. The parish of Northfield was anciently divided into several parts; the manors of Northfield and Selly (or Selley), and later Weoley, as well as the sub-manor of Middleton (later Haye and Middleton), and Middleton Hall was the manor house of Middleton. Middleton was the youngest of these sub-manors, with both Northfield and Selly being mentioned in the Domesday Book, but Middleton was formed in the latter part of the twelfth-century. It is thought to have been named after its position half-way between the villages of Northfield and Kings Norton.

Within Middleton were several farms including Rowheath Farm and Hay Green Farm; barns of the former surviving off Selly Oak Road and converted into housing. Middleton Hall itself had a sizeable farm attached called Middleton Hall Farm, which stretched along - what is now - Woodlands Park Road, out along Northfield Road, and down Popes Lane behind the Bunbury Road.

The Sub-Manor of Middleton

Ralph Paynel was the first known holder of Middleton in the late 1100s, and gave 'the land of Middletune and lahaie' to Bernard Paynel. 'lahaie' was later recorded as 'Le Hay', and was probably the Hay Green area.

In the 1200s the owners of Middleton took their name from the lands. John de Middleton was first mentioned in 1273, and the Middleton family held the lands until about the mid-1400s. After this, Middleton passed through the hands of several families.

Throughout the early centuries of Middleton's history there is no mention of a hall, although there would have been some form of manor house on the lands, most likely on the Woodlands Park Road/Bunbury Road site, which was near the roads running between Northfield and Kings Norton. This would have been a prime position to take goods to market, and to move around the rest of the manor.

Middleton Hall

The first known mention of 'Middleton Hall' was as 'Middleton Hall Farm' in 1596, when it was occupied by Henry Cookes. This was probably the timber-framed building which survived until the early 1800s, and was possibly moated, as traces of a moat were discovered during its demolition, but no archaeological survey was conducted so any evidence is now lost.

One hundred years after Cookes, the interior of Middleton Hall is brought to life through an inventory drawn-up after the death of its then occupant, Robert Fox. Fox was described as a 'yeoman', a gentleman farmer, and occupied Middleton Hall from at least 1684 till 1698, although in 1684 he would have been about 50 years old so he, and his wife Barbara, had probably been living there for several decades previously.

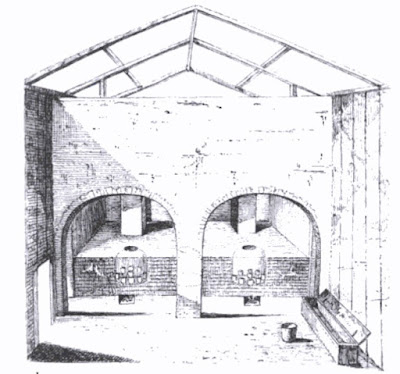

Fox's inventory shows that Middleton Hall had six rooms downstairs and five upstairs. Downstairs was a hall, parlour, kitchen, cheese chamber, back house and buttery. The back house had a malt mill, so was used for brewing, and the other rooms are pretty self explanatory. The parlour contained '2 looking-glasses' and the hall a 'brass candlestick' which were expensive items for the time, showing the wealth of the family. The five rooms upstairs all had beds in them, but some would probably have been used for entertaining guests, especially the chamber over the kitchen, which would have been warmer as it had a fire (meaning it had a brick chimney, another expense). This room also contained a 'closet of books', again showing a family of wealth as well as literacy (

see Fox's full inventory here).

Middleton Hall probably bore several similarities to

Selly Manor, which was moved from its original location in Selly Oak to its present site in Bournville Village between 1914 and 1916. Like Middleton Hall, Selly Manor was originally a manor-house, both were timber-built, and both a similar size, although Middleton Hall was possibly a little larger (although both probably had several additions made to them over the centuries). But the best way to get a sense of what Middleton Hall was like at this time is to visit Selly Manor (

visit details here).

In 1789, the occupant of Middleton Hall was William Henshaw, another yeoman running the farm as well as residing in the house. His diary for that year survives, and outlines the maintenance of the farm from winnowing grain and sowing peas, to helping 'Cherry' the cow give birth (other cows were called 'Kurley' and 'Prat'). His story will be added in the farm section,

below.

Henshaw's diary suggests that he struggled financially, and in the 1790s Middleton Hall Farm was bought by George Attwood, a wealthy ironmonger, and grandfather of Birmingham's first Member of Parliament, Thomas Attwood (whose statue was at the rear of the Town Hall, presumably to be replaced after the current works are finished). Attwood cared less about farming, and more that the land contained mineral deposits. He still owned the Hall in 1840, which was tenanted out to Robert Thornley.

It was perhaps Attwood, or one of his tenants, who remodelled Middleton Hall sometime in the first half of the nineteenth-century. The historian Leonard Day states that the front was 'encased in brick, which gave the Hall the external appearance of a gentleman's residence in the Victorian style'. Because the old building was beneath, the brick encasement (

see below) gives a sense of the shape of the timber-framed Hall.

|

| Click to enlarge. |

Photo: Sketch of Middleton Hall from a, now lost, photograph; showing the Victorian re-build from about the early 1800s.

The 1911 census noted that the Victorian Middleton Hall had twelve rooms (excluding workrooms, landing, hall, closets and bathrooms), so had been slightly extended from its 1690s predecessor.

The Hall was demolished in 1952.

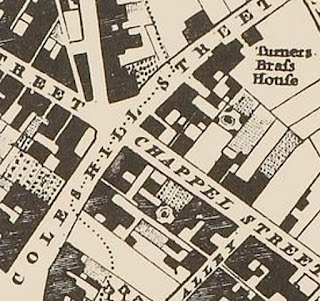

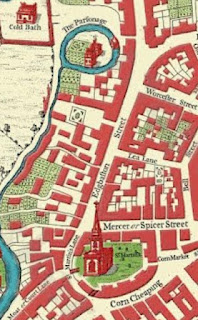

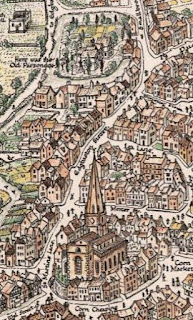

MAPS OF MIDDLETON HALL

|

| 1880s, click to enlarge. |

|

| 1900s, click to enlarge. |

|

| 1910s, click to enlarge. |

|

| 1930s, click to enlarge. |

|

| 1960s, click to enlarge. |