|

| Christ Church from New Street |

|

| Theatre Canopy and Statue |

|

| Child and Post |

|

| Town Hall Skyline |

|

| Portico and Pillars of Royal Society of Arts |

|

| Christ Church Spire |

|

| Lights |

|

| Christ Church from New Street |

|

| Theatre Canopy and Statue |

|

| Child and Post |

|

| Town Hall Skyline |

|

| Portico and Pillars of Royal Society of Arts |

|

| Christ Church Spire |

|

| Lights |

|

| Grosvenor House. A rainy day in June 2012. |

On the west corner of New Street and Bennett's Hill stands Grosvenor House, built in the early 1950s. There are two previous layers known for this site.

'one of Birmingham's earliest post-war buildings, Grosvenor House by Cotton, Ballard & Blow, 1951-3. The first designs of 1949 were plain. Manzoni asked for some improvement in the architectural treatment and the result has rows of sawtooth projections, little pointed iron ballustrades on the corner, and a brise-soleil. Flashy but undeniably effective'. From: Andy Foster, Birmingham, Pevsner Architectural Guide (London: Yale University Press, 2005), p. 111. |

| Chaucer's Head bookshop at 74 New Street, c. 1870s. Held at Birmingham Archive @ Library of Birmingham. |

See more of the Victorian Photo Album.

|

| The Hen and Chicken's on New Street, with King Edward's school to the right, c. 1808. Coaches would enter the rear stables through the arch. Held by Birmingham Museums. |

Were you at the “Hen and Chickens,” from which I write, however, you would be very well content with your quarters [...] I am surrounded by vases of beautiful flowers, many of them the choice productions of the green house in our rude climate, which ornament and perfume the halls and landings of the staircases, and impart an air bordering on elegance, to the general neatness and comfort of the establishment. The inn at which we are, is said to be the best in this great work-shop of iron and steel [...].*So noted Charles Samuel Stuart, an American visiting England and Ireland in 1832. He did not remain long in Birmingham, he felt it very modern, and the manufactures that made it worthy of visiting made it smokey and noisy. But Stuart did remain long enough to visit some manufactories before he left. He popped to the Pantechnetheca over the street, and up to St. Philip's church to visit the nearby premises of Edward Thomason on Church Street. Find details of his visit here.

as to the noise, never did I sleep at that enormous Hen and Chickens, to which usually my destiny brought me, but I had reason to complain that the discreet hen did not gather her vagrant flock to roost at less favourable hours. Till two or three, I was kept waking by those who were retiring; and about three commenced the morning functions of the porter, or of “boots”, or of “underboots”, who began their rounds for collecting the several freights for the Highflyer, or the Tally-ho, or the Bang-up, to all points of the compass, and too often (as much happen in such immense establishments) blundered into my room with the appalling, “Now, sir, the horses are coming out.” So that rarely, indeed, have I happened to sleep in Birmingham.**

|

| Front elevation and plan of stables for Hen and Chickens, 1836. Birmingham Archive: MS 3069/13/2/66. |

|

| Advert for Wm Waddell's Hen and Chickens, 1830-1835. Engraved by J. Garner from a drawing by Samuel Lines. Held by Birmingham Museums. |

Part three (of three parts) of Looking Through Windows (Greenery). See part one, here and part two, here. Please contact to use these cropped images in this way - mappingbirmingham@gmail.com

During the late Victorian period many of central Birmingham's poorer housing was earmarked for demolition in a drive to revamp the city centre and move those living in these houses out to newer homes in the outer parts of the town. Hundreds of photographs of 'slum housing' (Victorian terminology, not mine) were taken of the many courts of back to back housing in the town. These images were taken was to assert the reasoning for their demolition, that they were run down, so they "frame" the buildings to tell this story. This is only one story, though, as these buildings were filled with families living their lives and beautifying their homes, and if you zoom into the images you can find traces of this.

|

| Trade card for Billinge & Edwards on Snow Hill, c. 1810. Engraved by Cottrell. Held at Yale Center for British Art. B1978.43.956. |

|

| Held at Birmingham Archive in the Hutton Collection. |

Catherine Hutton (11 February 1756 to 13 March 1846) was part of the Birmingham Hutton family, the daughter of stationer, book seller and historian William Hutton and his wife Sarah Cock.*1* Catherine was a weaver of tales as well as a needlecrafter, a weaver of threads, and was putting pen to paper right up to her death at the age of 91. She was particularly a fan of Jane Austen, as she explained 'I have been going through a course of novels by lady authors, beginning with Mrs Brooke and ending with Miss Austen, who is my especial favourite. I had always wished, not daring to hope, that I might be something like Miss Austen; and, having finished her works, I took to my own, to see if I could find any resemblance'.*2* In 1813 she published her first novel, The Miser Married (1813), and published two subsequent novels, The Welsh Mountaineer (1817) and Oakwell Hall (1819). Catherine published other fiction and articles in magazines, and her published letters outline the life of a middle-class woman at this time.

See some of Catherine Hutton's writing: Hutton's Poem on Love & a Cosy Cottage (c. 1790s);The Miser Married (1813); The Welsh Mountaineer (1817) volume I.

The Hutton family business, a stationary and book shop, and home, above the shop, were attacked during the Birmingham riots of 1791. These riots targeted local dissenters and religious non-conformists, and the Hutton family were Unitarians. Their shop in Birmingham was burnt down and the family had to take shelter at their family home at Bennett's Hill, a few miles from the town. On hearing that rioters were on their way there too, the family had to quickly flee, and leave the house and their possessions to the mob.

The riots had been very hard for Catherine and she took to company less and less. Two years after the experience she wrote to a friend: 'Last Monday I broke the spell by visiting the Miss Mainwarings, and I was found so rusticated, so antiquated, that the first thing they did was to take my cap to pieces and make it up in a different form. Now, mark my resolution. I visited three families on the three following days, and I have engaged myself for two evenings next week. Be so good when you write to say something about fashion, that I, who used to be an example, may not be quite a scare-crow'.*3* In her isolation, Catherine took joy from tending to her garden, stating in the same letter that 'my inexhaustible fund of amusement is the garden' asking to be sent 'some flower seeds and bulbs. I should particularly like some feathered hyacinths'.*4*

Catherine's love gardening and flowers probably influenced her production of a patchwork bedcover surrounded with an array of appliqued flowers made in 1804. The design included jasmine, roses, tulips and lilac, and, as historian Elaine Mitchell notes, the 'appliqued plants delivered a cornucopia of botanical specimens from around the globe into the house' (see here).*4* It also brought some of Catherine's well-loved garden indoors and the needlework would have likely soothed her in the years she spent more isolated after the affects of the riots.

|

| Section of Catherine Hutton's bed cover (335cm by 362cm), 1804. Birmingham Museum Collections (20015.86.1). Photograph copyright Elaine Mitchell. |

Another of Catherine's surviving creations is a small purse made using simple lace-making techniques:

|

| Part of the Hutton collection at the Library of Birmingham. |

|

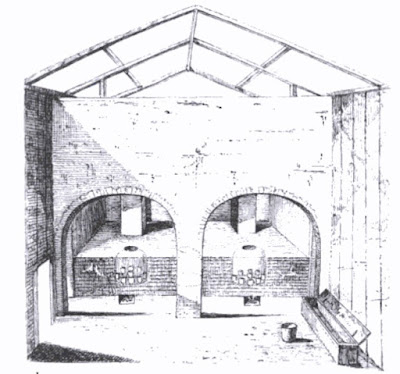

| Interior Mr. Turner's Brass Works from R. R. Angerstein's Illustrated Travel Diary, 1753-1755. |

The brass-works [...] belongs to Mr Turner and consists of nine furnaces with three built together in each of three separate buildings. The furnaces are heated with mineral coal, of which 15 tons is used for each furnace, and melting lasting ten hours. Each furnace holds nine pots, 14 inches high and nine inches diameter at the top. Each pot is charged with 41 pounds of copper and 50 pounds of calamine. Mixed with [char]coal. During charging I observed that a handful of coal and calamine was first placed on the bottom of the pot, then came the mixture, which was packed in tightly, followed by about a pound of copper in small pieces, and finally again coal and calamine without copper, covering the top. This procedure was said to lengthen the life of the pot both at the top and the bottom. [...] There are six workers for the nine furnaces and casting takes place twice every 24 hours.*1*

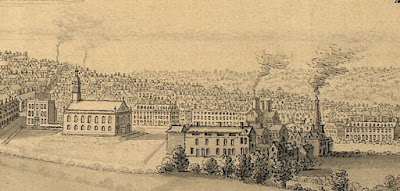

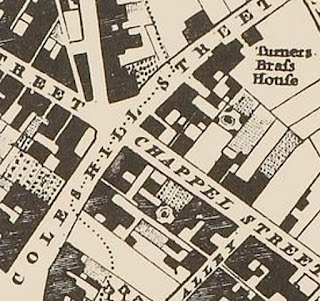

In 1782, William Hutton stated that the 'manufacture of brass was introduced by the family of Turner, about 1740, who erected those works at the south end of Coleshill-street' (see map, below). Although writing in 1783, Hutton first visited Birmingham in the 1740s and moved to the town in 1750, so would have some recollection of the early brass trade. He also said of the works that 'Under the black clouds which arose from this corpulent tunnel, some of the trades collected their daily supply of brass'.*2* Those 'black clouds' can be seen rising from the chimney's of Turner's 'Brass Works' on the 1753 East Prospect of Birmingham:

|

| St. Bartholomew's Chapel and smoking chimneys of the brass works, from the East Prospect of Birmingham (1753). |

|

| Section of the 1751 Map of Birmingham showing Coleshill Street and Turner's Brass House. |

Part two (of three parts) of Looking Through Windows (Greenery). See part one, here. Please contact to use these cropped images in this way - mappingbirmingham@gmail.com

During the late Victorian period many of central Birmingham's poorer housing was earmarked for demolition in a drive to revamp the city centre and move those living in these houses out to newer homes in the outer parts of the town. Hundreds of photographs of 'slum housing' (Victorian terminology, not mine) were taken of the many courts of back to back housing in the town. These images were taken was to assert the reasoning for their demolition, that they were run down, so they "frame" the buildings to tell this story. This is only one story, though, as these buildings were filled with families living their lives and beautifying their homes, and if you zoom into the images you can find traces of this. |

| St. Martin's Parsonage, from a drawing by David Cox and engraved by William Radcliffe, published 25 March 1827. Hand coloured later. |

St. Martin's Parsonage was demolished in 1826. The image above was drawn in about 1825 or 1826 by David Cox, and the original drawing is held by Birmingham Museums (see here). The Parsonage housed a long line of the rectors of St. Martin's, and stood a little distance from the church, up Edgbaston Street and at the base of Smallbrook Street.

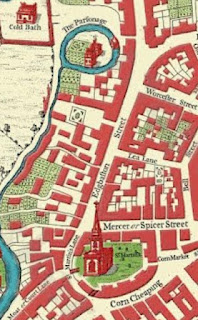

It was described in 1830, not long after its demolition, as an 'ancient, half-timbered edifice, coated with plaster' and that the 'entrance was through a wicket in the large doors of a long range of low building[s] next to the street'. The building had originally been encircled by a moat, as seen in snippets from the 1731 map of Birmingham below, but only dried-up parts of the moat remained when it was demolished despite the engraving including the moat filled with water.*1* An Act of Parliament was required for its demolition and acquired in 1825, which described the building as 'a most ancient and inconvenient building' which was 'very ill-suited for the residence of the rector'.*2* Parts of it were very ancient indeed.

|

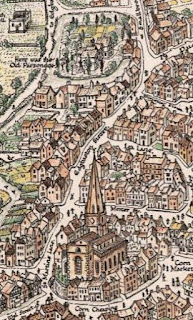

| Snippet from 1731 map showing St. Martin's church and parsonage. |

|

| Snippet from Bernard Sleigh's version of the 1731 map showing St. Martin's church and parsonage. |

|

| Close-up of the Parsonage from Bernard Sleigh's version of the 1731 map. |

|

| Charlotte Brontë's copy of the 1827 engraving, c. 1832. Private collection. |

|

| Original full photograph of 'slum housing', back of 52 & 54 Midland Street, late 1800s. |

|

| G. Houghton & Son on Birmingham's New Street, 1899. Printed by W. B. Hill & Co. |

|

| Demolition of the Theatre Royal in 1901. Held at Birmingham Archive. |

Towns have always been gathering points, and anciently the market was a primary draw, as well as other trade opportunities in manufacturing towns like Birmingham. Throughout the eighteenth century, though, the make-up of provincial towns, both architecturally and socially, was changing. Peter Borsay describes an ‘architectural renaissance’ beginning in the late 1600s and early 1700s, with provincial towns beginning ‘to appear visually more attractive and sophisticated’.[1] This occurred along with an increase in social activities as leisure became more in demand in the towns.[2] Wealthier residents and successful businessmen, with more free time, encouraged the building of increasing number of spaces within towns to be used for pleasure and entertainment, and these sites became focal points of the town. In Birmingham these included St. Philip’s with its elegant promenades and later the music festival, assembly rooms and later, in the early 1830s, the Town Hall.

One of Birmingham's most important buildings for its social life and entertainment was the Theatre on New Street, opened in 1774 (later patronised and called the Theatre Royal). The facade was built in 1780 by the renowned architect Samuel Wyatt and was described by one as ‘one of the handsomest theatre's anywhere’.*

|

| The theatre, later the Theatre Royal on New Street. Image possibly from about 1800. |

When it was built the Theatre stood opposite the other side of New Street, a row of unassuming houses including the Georgian Post Office and its yard. In the early 1820s, though, the site behind the Post Office was redeveloped and two new streets were made, Waterloo Street and Bennetts Hill (see here). Bennett's Hill was deliberately designed to create a frame for the the admired Theatre Royal, and that "frame" is still visible as the theatre was being demolished in the photograph, although the Georgian Theatre Royal itself was very soon to be gone. A new Theatre Royal was to be built, which Bennetts Hill framed for a short time, and now that has been demolished too.

Framing tells us where to look. It takes a section of something, like the urban landscape, and singles it out for particular contemplation, and this is evident in the case of New Street's theatre. One commentator regretted, in 1830, that the theatre had not been built further back from the other buildings on the street to further enhance its prospect, but he cheerfully noted that it could be seen with full effect from the road called Bennett’s Hill which faced it.*

------------

NOTES

[1], [2] Peter Borsay, The English Urban Renaissance

[*] Other and full references on request.

~ The building on the right of the photograph is the Bennett's Hill face of the Post Office Building (never actually a post office but replacing the Georgian cottage post office, hence the name) designed by Charles Edge, and erected in 1842.

|

| Old Farrier's Arms, c. 1880s or 1890s. Held by Birmingham Archive - WK/B11/1264. |

|

| New Street, 1902. Held at Birmingham Archive. |

|

| Masks and props from the Theatre Royal. Taken shortly before demolition. |

|

| The corner of Congreve Street and Ann Street (looking up Ann Street), May 1867. Held at Birmingham Archive. |

|

| Aston Church in Aston, near Birmingham, with the River Tame nearby, before the railway cut it away from Aston village, c. 1830s. |

|

| Looking down Aston Street from outside the Aston Tavern in 1897, with the Holte Almshouses on the other side. |

|

| Holte Almshouses. |

|

| Aston Street with the Old Aston Tavern on the left, during the days when the gardens behind led to a picturesque river remnant; the Serpentine. |

|

| The Old Aston Tavern shortly before demolition and rebuild, with the spire of Aston Church behind. |

|

| Aston Hall with the Grand Junction Railway passing. |

|

| Birmingham Onion Fair Week. Birmingham Gazette, 1 October 1915. |